windows wiki

clean and backup windows

settings–system–about–(right)advan_system_setting

Click the Windows menu and type ‘Disk Cleanup’ in the search bar to get started.

To disable transparency effects, open the Windows menu and type ‘Make Start, taskbar and Action Center transparent’. This will pull up the Color Settings. From here you can choose to switch off transparency.

To reset your PC, go to Start > Settings > Update & Security > Recovery > Reset this PC > Get Started. Then, select Keep my files, choose cloud or local, change your settings, and set Restore preinstalled apps? to No.

One of the benefits of this new approach is that Windows attempts to recover from a previously created system image or – failing that – using a special series of install files that download the latest version of Windows during the reinstall process.

type: recovery drive into the search field on the taskbar and hit Enter. Or select the option to create from the results at the top or click Open from the app description section.

A system image is another way to say “full backup,” as it contains a copy of everything on the computer, including the installation, settings, apps, and files.

Quick note: You’ll also receive a prompt to create a system repair disc, but because most devices no longer include an optical drive, you can skip it. If you have to restore the machine, you can use a USB installation media to access the recovery enviroment.

Connect the drive with the full backup to the device.

Connect the Windows 10 USB bootable drive to the computer.

On the “Windows Setup” page, click the Next button.

Click the Repair your computer option from the bottom-left corner of the screen.

Click the Troubleshoot option.

The downside is that personal files and desktop apps won’t come along for the ride, but you should already be backing up your personal files separately. At the very least, a recovery drive wil bring Windows 10 back to a bootable and working state.

However, if preserving your personal files is absolutely necessary, a System Image Backup is another recovery option. This method allows you to create an image of your entire Windows environment, including your personal files and applications.

windows desktop management

multiple desktops

The idea of virtual desktops is straightforward: Instead of just a single desktop, you create a second, third, fourth, and so on. On each desktop, you arrange individual programs or combinations of apps you want to use for a specific task. Then, when it’s time to tackle one of those tasks,

you switch to the virtual desktop and get right to work.

windows snap

Drag the top window border (not the title bar) to the top edge of the screen, or drag the

bottom border to the bottom edge of the screen. With either action, when you reach the

edge, the window snaps to full height without changing its width. When you drag the

border away from the window edge, the opposite border snaps to its previous position.

Snap side-by-side Windows at different widths

The secret is to snap the first window and immediately drag its inside edge to adjust the

window to your preferred width. Now grab the title bar of the window you want to see

alongside it and snap it to the opposite edge of the display. The newly snapped window

expands to fill the space remaining after you adjusted the width of the first window.

Keyboard shortcuts and gestures for resizing and moving windows

| Task | Keyboard shortcut | Gesture |

|---|---|---|

| Maximize window | Windows key+ Up Arrow | Drag title bar to top of screen |

| Resize window to full screen height without changing its width | Shift+Windows key+Up Arrow | Drag top or bottom border to edge of screen |

| Restore a maximized or full-height window | Windows key+Down Arrow | Drag title bar or border away from screen edge |

| Minimize a restored window | Windows key+Down Arrow | Click the Minimize button |

| Snap to the left half of the screen | Windows key+Left Arrow* | Drag title bar to left edge |

| Snap to the right half of the screen | Windows key+Right Arrow* | Drag title bar to right edge |

| Move to the next virtual desktop | Ctrl+Windows key+Left/Right Arrow | Three-finger swipe on precision touchpad; none for mouse |

| Move to the next monitor | Shift+Windows Key+Left/Right Arrow | Drag title bar |

| Minimize all windows except the active window (press again to restore windows previously minimized with this shortcut) | Windows key+Home | “Shake” the title bar |

| Minimize all windows | Windows key+M | |

| Restore windows after minimizing | Shift+Windows key+M |

disk management

Windows key+X Open the Quick Link menu

right click windows start icon

extend/shrink volumes

adjust the sizes of your partitions. increase or reduce the size of the seleted partition

扩展/压缩 卷

virtual file library

library is colletion of certain kinds of files based on a theme. they work in virtual manner: the files aren’t literally stored in these libraries, they are merely colloted and linked to the library.

taskbar jump lists

taskbar jump lists for quick access to documents and folders

a jump list is the official name of the menu that appears when you right-click to a taskbar button.

Each Jump List includes commands to open the program, to pin the program to the taskbar (or unpin it), and to close all open windows represented by the button.

In addition, for programs developed to take advantage of this feature, Jump Lists can include shortcuts to common tasks that can be performed with that program,

such as New Window or New InPrivate Window on a Microsoft Edge Jump List.

For Microsoft Office programs, Adobe Acrobat, and other similarly document-centric programs, Jump Lists also typically include links

to recently opened files.

font smoothing

using font smoothing to make text easier on the eyes

to check or change your font-somoothing settings, type cleartype in the search box and then click Ajust ClearType Text

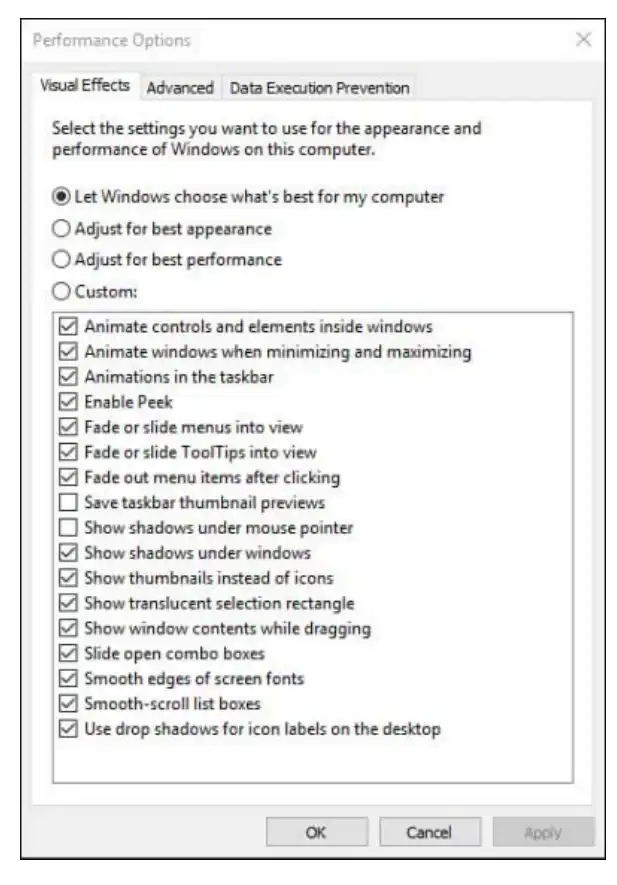

performance

On modern hardware with even a moderate graphics processor, these options make little or

no difference in actual performance. The loss of animation can be disconcerting, in fact, as you

wonder where a particular item went when you minimized it. These options offer the most payoff on older devices with underpowered graphics hardware.

file explore

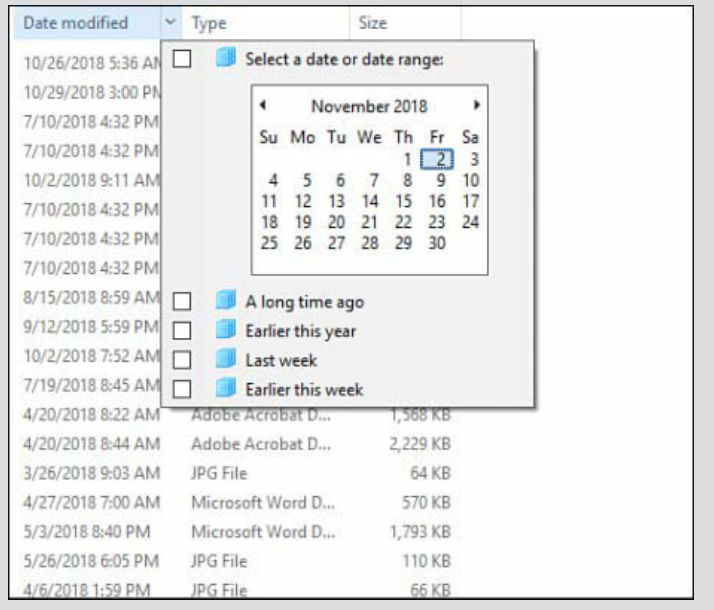

Use the date navigator to zoom through time

If you click a date heading, the filter options display a date navigator like the one shown

next, with common date groupings available at the bottom of the list. You can also click

Select A Date Or Date Range and use the calendar to filter the file list that way

Use check boxes to simplify file selection

File Explorer offers two modes of file and folder selection—with and without check boxes.

You can switch between them by means of the Item Check Boxes command on the View tab.

With check boxes on, you can select multiple items that are not adjacent to one another by

clicking or tapping the check box for each one in turn; to remove an item from the selection,

clear its check box. In either case, there’s no need to hold down the Ctrl key

To scrub a file of unwanted metadata, select one or more files in File Explorer, click

Home > Properties > Remove Properties.

explore search

Whatever text you type as a search term must appear at the beginning of a word, not in

the middle. Thus, entering des returns items containing the words desire, destination, and

destroy but not undesirable or saddest.

Search terms are not case sensitive. Thus, entering Bott returns items with Ed Bott as a tag

or property, but the results also include files containing the words bottom and bottle.

To search for an exact phrase, enclose the phrase within quotation marks. If you enter two

or more words without using quotes, the search results list includes items that contain all

of the words individually.

Advanced queries support the following types of search parameters, which can be combined

using search operators:

● File contents. Keywords, phrases, numbers, and text strings

● Kinds of items. Folders, documents, pictures, music, and so on

● Data stores. Specific locations in the Windows file system containing indexed items

● File properties. Size, date, tags, and so on

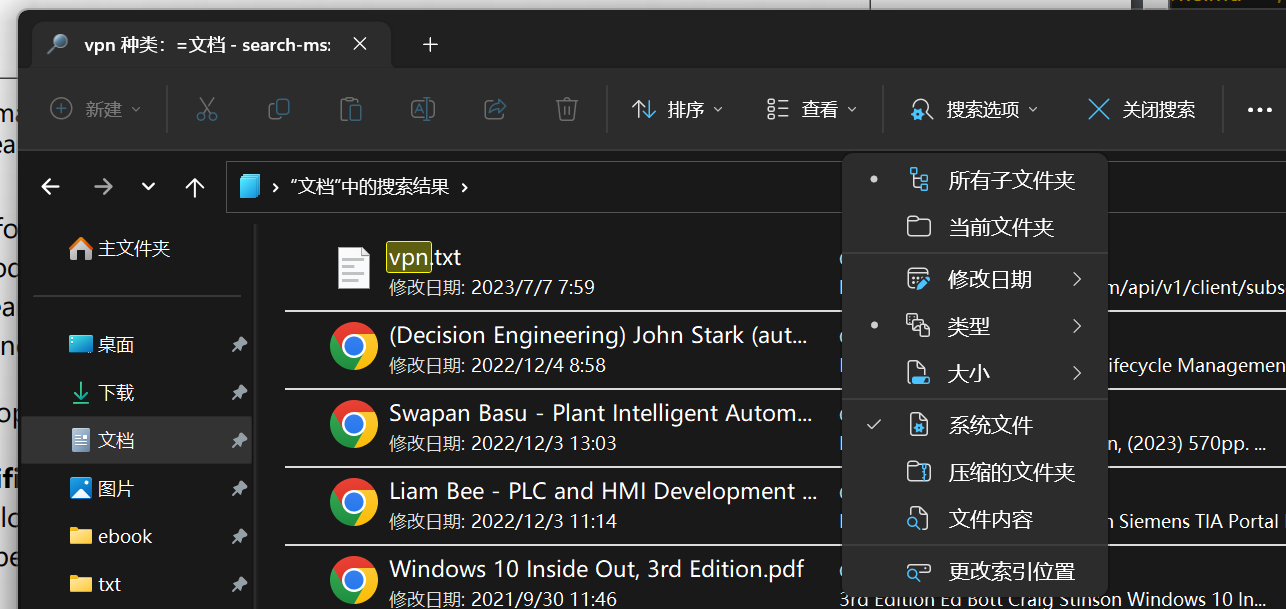

Searching by item type or kind

To search for files with a particular file name extension, you can simply enter the extension in

the search box, like this:

.ext

(Note that this method of searching does not work for .exe or .msc files.) The results include files

that incorporate the extension in their contents as well as in their file names—which might or

might not be what you want. You’ll get a more focused search by using the ext: operator, including an asterisk wildcard and a period like this:

ext:.txt

NOTE

As with many properties, you have more than one way to specify an exact file name

extension. In addition to ext:, you can use fileext:, extension:, or fileextension:.

File name extensions are useful for some searches, but you’ll get even better results using two

different search properties: Type and Kind. The Type property limits your search based on the

value found in the Type field for a given object. Thus, to look for files saved in any Microsoft

Excel format, type this term in the search box:

type:excel

To find any music file saved in MP3 format, type this text in the search box:

type:mp3

To constrain your search to groups of related file types, use the Kind property, in the syntax

kind:=value. Enter kind:=doc, for example, to return text files, Microsoft Office documents,

Adobe Acrobat documents, HTML and XML files, and other document formats. This search term

also accepts folder, pic, picture, music, song, program, and video as values to search for.

Changing the scope of a search

You can specify a folder or library location by using folder:, under:, in:, or path:. Thus,

folder:documents restricts the scope of the search to your Documents library, and in:videos mackie finds all files in the Videos library that contain Mackie in the file name or any property.

Searching for item properties

You can search on the basis of any property recognized by the file system. (The list of available

properties for files is identical to the ones we discuss in “Layouts, previews, and other ways to

arrange files” in Chapter 9.) To see the whole list of available properties, switch to Detail view in

File Explorer, right-click any column heading, and then click More. The Choose Details dialog

box that appears enumerates the available properties.

When you enter text in the search box, Windows searches file names, all properties, and indexed

content, returning items where it finds a match with that value. That often generates more

search results than you want. To find all documents of which Jean is the author, omitting documents that include the word Jean in their file names or content, you type author:jean in the

search box. (To eliminate documents authored by Jeanne, Jeannette, or Jeanelle, add an equal

sign and enclose jean in quotation marks: author:=”jean”.)

When searching on the basis of dates, you can use long or short forms, as you please. For example, the search values

modified:9/29/16

and

modified:09/29/2016

are equivalent. (If you don’t mind typing the extra four letters, use datemodified: instead.)

To search for dates before or after a particular date, use the less-than (<) and greater-than (>)

operators. For example,

modified:>09/30/2015

searches for dates later than September 30, 2015. Use the same two operators to specify file

sizes below and above some value.

Use two periods to search for items within a range of dates. To find files modified in September

or October 2016, type this search term in the Start menu search box:

modified:9/1/2016..10/31/2016

You can also use ranges to search by file size. The search filters suggest some common ranges

and even group them into neat little buckets, so you can type size: and then click Medium to

find files in the range 100 KB to 1 MB.

Again, don’t be fooled into thinking that this list represents the full selection of available sizes.

You can specify an exact size range—using operators such as >, >=, <, and <=. (Also, you can use

the “..” operator.) For example, size:0 MB..1 MB is the same as size:<=1 MB. You can specify

values using bytes, KB, MB, or GB.

Using multiple criteria for complex searches

You can use the Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT to combine or negate criteria in the

search box. These operators need to be spelled in capital letters (or they will be treated as ordinary text). In place of the AND operator, you can use a plus sign (+), and in place of the NOT

operator, you can use a minus sign (–). You can also use parentheses to group criteria; items

in parentheses separated by a space use an implicit AND operator. Table 10-1 provides some

examples of combined criteria.

Table 10-1 Some examples of complex search values

| This search value | Returns |

|---|---|

| Siechert AND Bott | Items in which at least one indexed element (property,file name, or an entire word within its contents) begins with or equals Siechert and another element in the same item begins with or equals Bott |

| title:(“report” NOT draft) | Items in which the Title property contains the word report and does not contain a word that begins with draft |

| tag:tax AND author:Doug | Items authored by Doug that include Tax in the Tags field |

| tag:tax AND author:(Doug OR Craig) AND modified:<1/1/18 | Items authored by Doug or Craig, last modified before January 1, 2018, with Tax in the Tags field |

NOTE

When you use multiple criteria based on different properties, an AND conjunction is

assumed unless you specify otherwise. The search value tag:Ed Author:Carl is equivalent

to the search value tag:Ed AND Author:Carl.

Using wildcards and character-mode searches

File-search wildcards can be traced back to the dawn of Microsoft operating systems, well

before the Windows era. In Windows 10, two of these venerable operators are alive and well:

● The asterisk (), also known as a star operator, can be placed anywhere in the search string

and will match zero, one, or any other number of characters. In indexed searches, which

treat your keyword as a prefix, this operator is always implied at the end; thus, a search for

voice turns up voice, voices, and voice-over. Add an asterisk at the beginning of the search

term (**voice), and your search also turns up any item containing invoice or invoices. You

can put an asterisk in the middle of a search term as well, which is useful for searching

through folders full of data files that use a standard naming convention. If all your

invoices start with INV, followed by an invoice number, followed by the date (INV-0038-

20180227, for example), you can produce a quick list of all 2018 invoices by searching for

INV*2018*.

● The question mark (?) is a more focused wildcard. In index searches, it matches exactly

one character in the exact position where it’s placed. Using the naming scheme defined

in the previous item, you can use the search term filename:INV-????-2018* to locate any

file in the current location that has a 2018 date stamp and an invoice number (between

hyphens) that is exactly four characters long.

To force Windows Search to use strict character matches in an indexed location, type a tilde (~)

as the first character in the search box, followed immediately by your term. If you open your

Documents library and type ~??v in the search box, you’ll find any document whose file name

contains any word that has a v in the third position, such as saved, level, and, of course, invoice.

This technique does not match on file contents.

Sharing files, printers, and other resources over a local network

Understanding sharing and security models in Windows

Much like Windows 7, Windows 10 offers two ways to share file resources, whether you’re doing

so locally or over the network:

● Public folder sharing. When you place files and folders in your Public folder or its subfolders, those files are available to anyone who has a user account on your computer.

Each person who signs in has access to his or her own profile folders (Documents, Music,

and so on), and everyone who signs in has access to the Public folder. (You need to dig a

bit to find the Public folder, which—unlike other profiles—doesn’t appear under Desktop

in the left pane of File Explorer. Navigate to C:\Users\Public. If you use the Public folder

often, pin it to the Quick Access list in File Explorer.)

By default, all users with an account on your computer can sign in and create, view, modify, and delete files in the Public folders. The person who creates a file in a Public folder (or

copies an item to a Public folder) is the file’s owner and has Full Control access. All others

who sign in locally have Modify access.

Settings in Advanced Sharing Settings (accessible from Settings > Network & Internet,

discussed in the next section) determine whether the contents of your Public folder are

made available on your network and whether entering a user name and password is

required for access. If you turn on password-protected sharing, only network users who

have a user account on your computer (or those who know the user name and password

for an account on your computer) can access files in the Public folder. Without passwordprotected sharing, everyone on your network has access to your Public folder files if you

enable network sharing of the Public folder.

You can’t select which network users get access, nor can you specify different access levels

for different users. Sharing via the Public folder is quick and easy—but it’s inflexible.

● Advanced sharing. By choosing to share folders or files outside the Public folder, you

can specify precisely which user accounts are able to access your shared data, and you

can specify the types of privileges those accounts enjoy. You can grant different access

privileges to different users. For example, you might enable some users to modify shared

files and create new ones, enable other users to read files without changing them, and

lock out still other users altogether.

You don’t need to decide between sharing the Public folder and sharing specific folders,

because you can use both methods simultaneously. You might find that a mix of sharing styles

works best for you; each has its benefits:

● Sharing specific folders is best for files you want to share with some users but not with

others—or if you want to grant different levels of access to different users

● Public folder sharing provides a convenient, logical way to segregate your personal documents, pictures, music, and so on from those you want to share with everyone who uses your

computer or your network.

Configuring your network for sharing

If you plan to share folders and files with other users on your network, you need to take a few preparatory steps. (If you plan to share only with others who use your computer by signing in locally,

you can skip these steps. And if your computer is part of a domain, some of these steps—or their

equivalent in the domain world—must be done by an administrator on the domain controller. We

don’t cover those details in this book.)

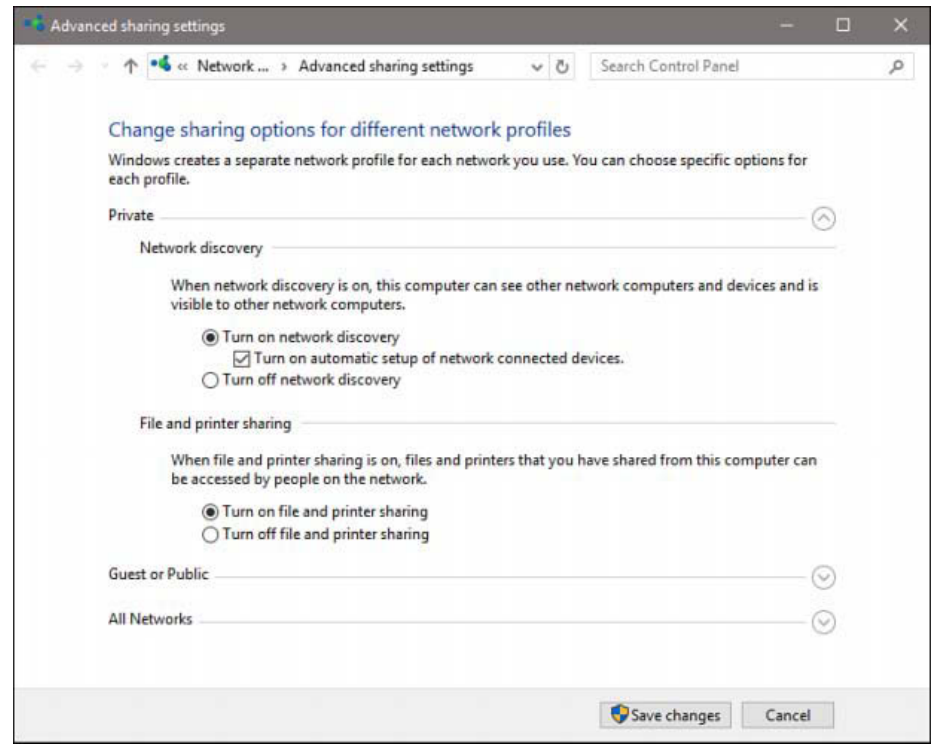

- Be sure that all computers use the same workgroup name. With modern versions of

Windows, this step isn’t absolutely necessary, although it does improve network discovery

performance. - Be sure that your network’s location is set to Private. This setting makes it possible for

other users to discover shared resources and provides appropriate security for a network in a

home or an office. For details, see “Setting the network location,” earlier in this chapter. - Be sure that Network Discovery is turned on. This should happen automatically when

you set the network location to Private, but you can confirm the setting—and change it if

necessary—in Advanced Sharing Settings, which is shown in Figure 13-18. To open Advanced

Sharing Settings, go to Settings > Network & Internet; on the Status page, click Sharing Options.

Figure 13-18 After you review settings for the Private profile, click the arrow by All Networks

(below Guest Or Public) to see additional options.

- Select your sharing options. In Advanced Sharing Settings, make a selection for each of

the following network options. You’ll find the first option under the Private profile; to view

the remaining settings, expand All Networks.

■ File And Printer Sharing. Turn on this option if you want to share specific files or

folders, the Public folder, or printers; it must be turned on if you plan to share any

files (other than media streaming) over your network.

The mere act of turning on file and printer sharing does not expose any of your

computer’s files or printers to other network users; that occurs only after you make

additional sharing settings.

■ Public Folder Sharing. If you want to share items in your Public folder with all

network users (or, if you enable password-protected sharing, all users who have a

user account and password on your computer), turn on Public folder sharing. If you

do so, network users will have read/write access to Public folders. With Public folder

sharing turned off, anyone who signs in to your computer locally has access to Public folders, but network users do not.

■ Media Streaming. Turning on media streaming provides access to pictures, music,

and video through streaming protocols that can send media to computers or to

other media playback devices. In an era where most people stream their music

collections from services like Spotify, this option is increasingly esoteric and nearly

irrelevant.

■ File Sharing Connections. Leave this option set to 128-bit encryption, which has

been the standard for most of this century.

■ Password Protected Sharing. When password-protected sharing is turned on,

network users cannot access your shared folders (including Public folders, if shared)

or printers unless they can provide the user name and password of a user account

on your computer. With this setting enabled, when another user attempts to access

a shared resource, Windows sends the user name and password that the person

used to sign in to her own computer. If that matches the credentials for a local user

account on your computer, the user gets immediate access to the shared resource

(assuming permissions to use the resource have been granted to that user account).

If either the user name or the password does not match, Windows asks the user to

provide credentials.

With password-protected sharing turned off, Windows does not require a user

name and password from network visitors. Instead, network access is provided by

using the Guest account. As we explain in Chapter 11, “Managing user accounts,

passwords, and credentials,” this account isn’t available for interactive use but can

handle these tasks in the background. - Configure user accounts. If you use password-protected sharing, each person

who accesses a shared resource on your computer must have a user account on your

computer. Use a Microsoft account or, for a local account, use the same user name as

that person uses on his or her own computer and the same password as well. If you do

that, network users will be able to access shared resources without having to enter their

credentials after they’ve signed in to their own computer.

Sharing files and folders from any folder

Whether you plan to share files and folders with other people who share your computer or

those who connect to your computer over the network (or both), the process for setting up

shared resources is the same as long as the Sharing Wizard is enabled. We recommend you use

the Sharing Wizard even if you normally disdain wizards. It’s quick, easy, and certain to make

all the correct settings for network shares and NTFS permissions—a sometimes-daunting task

if undertaken manually. After you configure shares with the wizard, you can always dive in and

make changes manually if you need to. (Although it’s possible to use the Advanced Sharing

options to configure network sharing independently of NTFS permissions, we don’t recommend

that technique and do not cover it in this edition.)

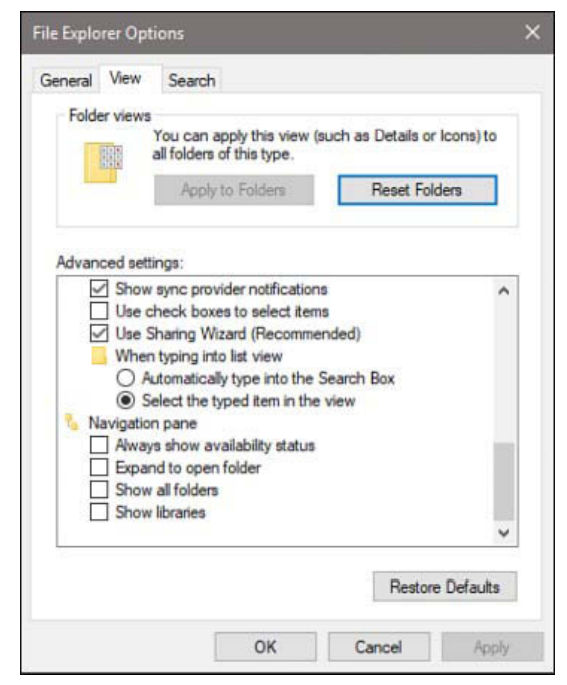

To be sure the Sharing Wizard is enabled, open File Explorer Options. (Type folder in the search

box, and then choose File Explorer Options. Or, in File Explorer, click View > Options.) In the dialog box that appears, shown next, click the View tab. Near the bottom of the Advanced Settings

list, see that Use Sharing Wizard (Recommended) is selected:

With the Sharing Wizard at the ready, follow these steps to share a folder or files:

- In File Explorer, select the folders or files you want to share. (You can select multiple

objects.) - Right-click and choose Give Access To > Specific People. (In versions before 1709, the

command is Share With.) Alternatively, click or tap the Share tab and then click Specific

People in the Share With box. You might need to click the arrow in the Share With box to

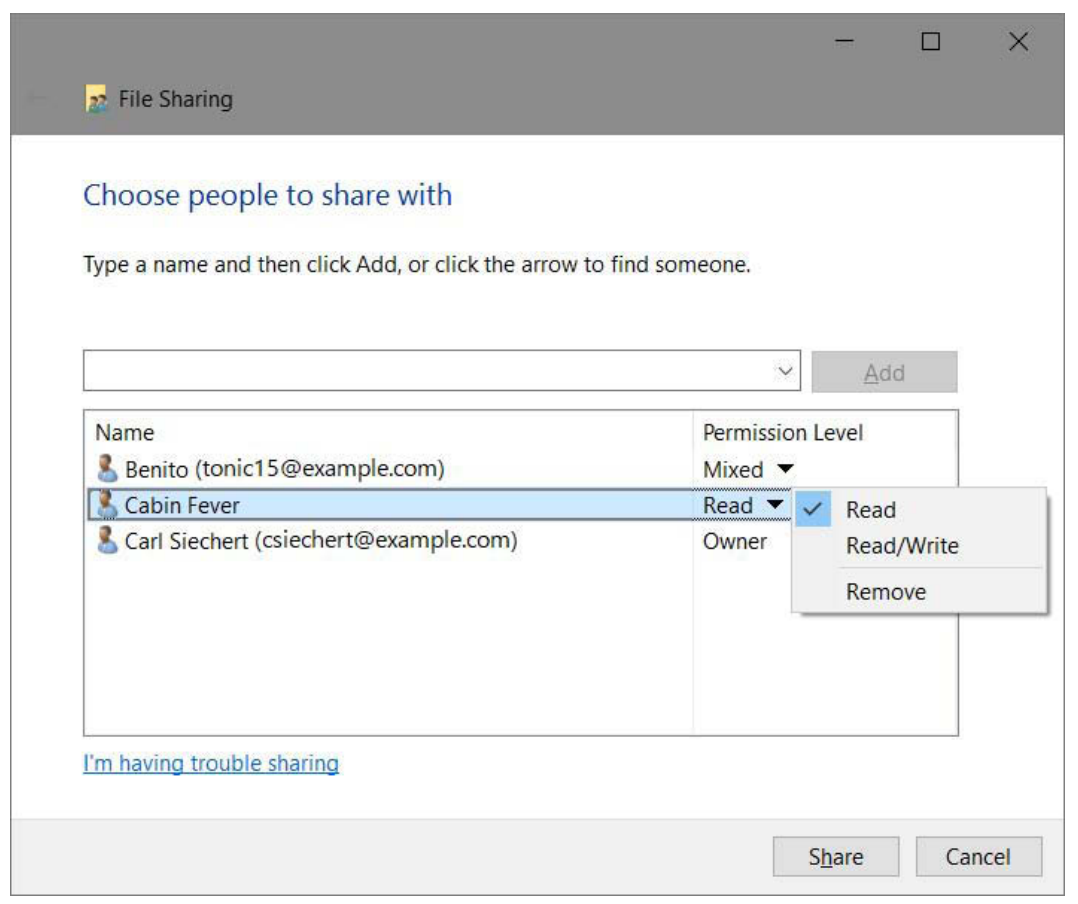

display Specific People. The File Sharing dialog box appears, as shown in Figure 13-19.

Figure 13-19 For each name in the list other than the owner, you can click the arrow to set the

access level—or remove that account from the list.

3. In the entry box, enter the name or Microsoft account for each user with whom you want

to share. You can type a name in the box or click the arrow to display a list of available

names; then click Add. Repeat this step for each person you want to add.

The list includes all users who have an account on your computer, plus Everyone. Guest

is included if password-protected sharing is turned off. If you want to grant access to

someone who doesn’t appear in the list, click Create A New User, which takes you to User

Accounts in Control Panel.

NOTE

If you select Everyone and you have password-protected sharing enabled, the user

must still have a valid account on your computer. However, if you turned off passwordprotected sharing, network users can gain access only if you grant permission to

Everyone or to Guest.

For each user, select a permission level. Your choices are

■ Read. Users with this permission level can view shared files and run shared programs, but they cannot change or delete files. Selecting Read in the Sharing Wizard is equivalent to setting NTFS permissions to Read & Execute.

■ Read/Write. Users assigned the Read/Write permission have the same privileges you do as owner: they can view, change, add, and delete files in a shared folder. Selecting Read/Write sets NTFS permissions to Full Control for this user.NOTE

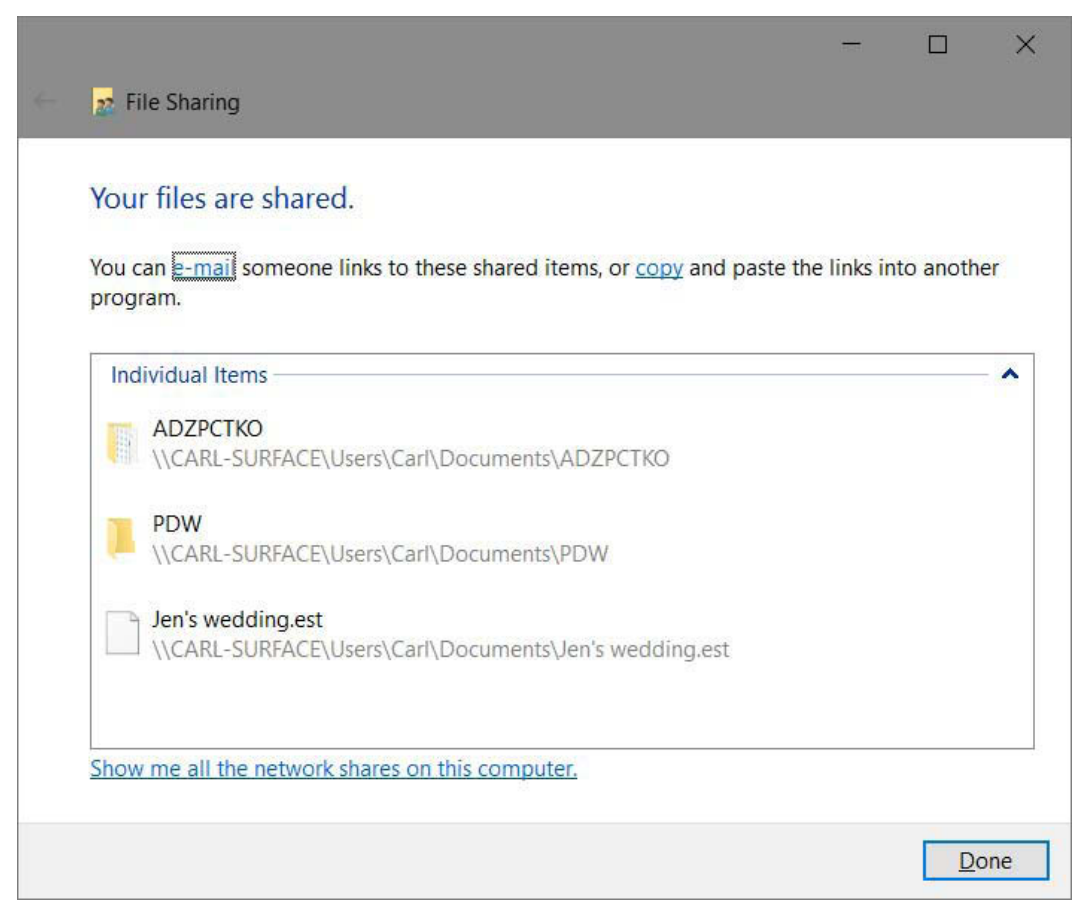

You might see other permission levels if you return to the Sharing Wizard after you set up sharing. Contribute indicates Modify permission. Custom indicates NTFS permissions other than Read & Execute, Modify, or Full Control. Mixed appears if you select multiple items and they have different sharing settings. Owner, of course, identifies the owner of the item.Click Share. After a few moments, the wizard displays a page like the one shown in Figure

13-20.In the final step of the wizard, you can do any of the following:

■ Send an email message to the people with whom you’re sharing. The message

includes a link to the shared items.

■ Copy the network path to the Clipboard. This is handy if you want to send a link via

another application, such as a messaging app. (To copy the link for a single item in

a list, right-click the share name and choose Copy Link.)

■ Double-click a share name to open the shared item.

■ Open File Explorer with your computer selected in the Network folder, showing

each network share on your computer.

When you’re finished with these tasks, click Done.

Figure 13-20 The Sharing Wizard displays the network path for each item you shared.

Creating a share requires privilege elevation, but after a folder has been shared, the share is

available to network users no matter who is signed in to your computer—or even when nobody

is signed in.

Inside OUT

Use advanced sharing to create shorter network paths

Confusingly, when you share one of your profile folders (or any other subfolder of

%SystemDrive%\Users), Windows creates a network share for the Users folder—not for

the folder you shared. This behavior isn’t a security problem; NTFS permissions prevent

network users from seeing any folders or files except the ones explicitly shared. But it

does lead to some long Universal Naming Convention (UNC) paths to network shares.

For example, sharing the PDW subfolder of Documents (as shown in Figure 13-16) creates the network path \CARL-SURFACE\Users\Carl\Documents\PDW. If this same folder

had been anywhere on your computer outside the Users folder, no matter how deeply

nested, the network path would instead be \CARL-SURFACE\PDW. Other people to

whom you granted access wouldn’t need to click through a series of folders to find the

files in the intended target folder.

Network users, of course, can map a network drive or save a shortcut to your target

folder to avoid this problem. But you can work around it from the sharing side, too: Use

advanced sharing to share the folder directly. (Do this after you’ve used the Sharing

Wizard to set up permissions.) And while you’re doing that, be sure the share name you

create doesn’t have spaces. Eliminating them makes it easier to type a share path that

works as a link.

Stopping or changing sharing of a file or folder

If you want to stop sharing a particular shared file or folder, select it in File Explorer and on the

Share tab, click Remove Access (Stop Sharing in versions before 1709). Or right-click and choose

Give Access To > Remove Access. Doing so removes access control entries that are not inherited.

In addition, the network share is removed; the folder will no longer be visible in another user’s

Network folder.

To change share permissions, right-click and choose Give Access To > Specific People. In the

File Sharing dialog box (shown earlier in Figure 13-15), you can add users, change permissions,

or remove users. (To stop sharing with a user, click the permission level by the user’s name and

choose Remove.)

Working with mapped network folders

Mapping a network folder makes it appear to applications as though the folder is part of your

own computer. Windows assigns a drive letter to the mapped folder, making the folder appear

like an additional hard drive. You can still access a mapped folder in the conventional manner by navigating to it through the Network folder. But mapping gives the folder an alias—the

assigned drive letter—that provides an alternative means of access.

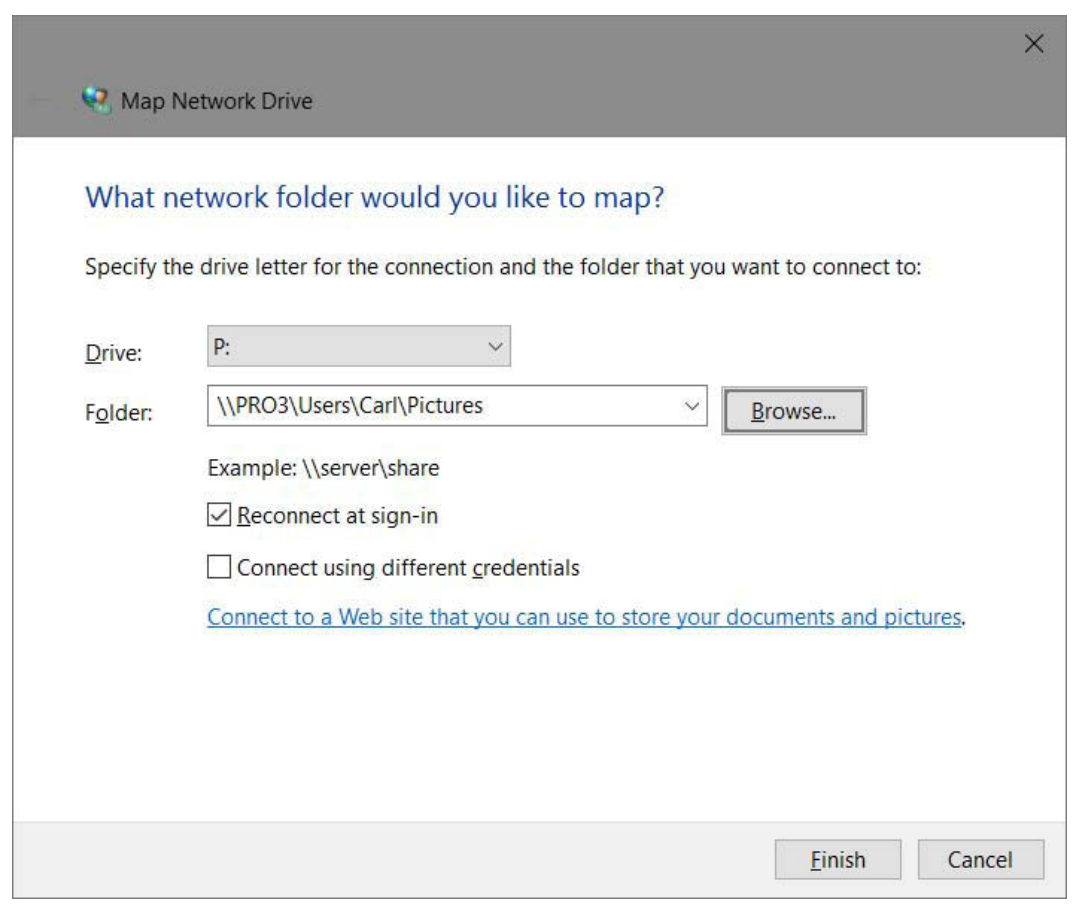

To map a network folder to a drive letter, follow these steps:

Open This PC in File Explorer, and on the ribbon’s Computer tab, click Map Network Drive.

(Alternatively, after you open a computer in the Network folder, right-click a network

share and choose Map Network Drive.)

Select a drive letter from the Drive list. You can choose any letter that’s not already in use.

In the Folder box, type the path to the folder you want or, more easily, click Browse and

navigate to the folder.Select Reconnect At Sign-In if you want Windows to connect to this shared folder

automatically at the start of each session.If your regular sign-in account doesn’t have permission to connect to the resource, select

Connect Using Different Credentials. (After you click Finish, Windows asks for the user

name and password you want to use for this connection.)Click Finish.

In File Explorer, the “drive” appears under This PC.

If you change your mind about mapping a network folder, right-click the folder’s icon in your

This PC folder. Choose Disconnect on the resulting shortcut menu, and the connection will be

severed.

Connecting to a network printer

To use a printer that has been shared, open the Network folder in File Explorer and double-click

the name of the server to which the printer is attached. If the shared printers on that server

are not visible, return to the Network folder, click to select the server, and then, on the ribbon’s

Network tab, click View Printers. Right-click the printer and choose Connect. Alternatively, from

the Devices And Printers folder, click Add A Printer and use the Add Printer Wizard to add a network printer.

disk part

UNDERSTANDING DISK-MANAGEMENT TERMINOLOGY

The current version of Disk Management has simplified somewhat the arcane language of

disk administration. Nevertheless, it’s still important to have a bit of the vocabulary under

your belt. The following terms and concepts are the most important:

● Volume. A volume is a disk or subdivision of a disk that is formatted and available

for storage. If a volume is assigned a drive letter, it appears as a separate entity in File

Explorer. A hard disk can have one or more volumes.

● Mounted drive. A mounted drive is a volume that is mapped to an empty folder on

an NTFS-formatted disk. A mounted drive does not get a drive letter and does not

appear separately in File Explorer. Instead, it behaves as though it were a subfolder on

another volume.

● Basic disk and dynamic disk. The two principal types of hard-disk organization in

Windows are called basic and dynamic:

■ A basic disk can be subdivided into as many as four partitions. (Disks that

have been initialized using a GUID Partition Table can have more than four.)

All volumes on a basic disk must be simple volumes. When you use Disk Management to create new simple volumes, the first three partitions it creates are

primary partitions. The fourth is created as an extended partition using all

remaining unallocated space on the disk. An extended partition can be organized into as many as 2,000 logical disks. In use, a logical disk behaves exactly

like a primary partition.

■ A dynamic disk offers organizational options not available on a basic disk. In

addition to simple volumes, dynamic disks can contain spanned or striped

volumes. These last two volume types combine space from multiple disks. We

expect that very few of our readers will ever use dynamic disks.

● Simple volume. A simple volume is a volume contained entirely within a single

physical device. On a basic disk, a simple volume is also known as a partition.

● Spanned volume. A spanned volume is a volume that combines space from physically separate disks, making the combination appear and function as though it were a

single storage medium.

● Striped volume. A striped volume is a volume in which data is stored in 64-KB strips

across physically separate disks to improve performance.

● Active partition, boot partition, and system partition. The active partition is the

one from which an x86-based computer starts after you power it up. The first physical hard disk attached to the system (Disk 0) must include an active partition. The

boot partition is the partition where the Windows system files are located. The system partition is the partition that contains the bootstrap files that Windows uses to

start your system and display the boot menu.

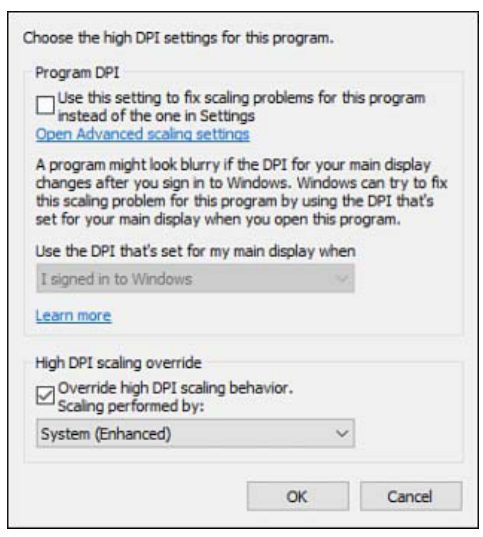

Beginning with version 1703, Windows 10 includes new display code that improves rendering for some older desktop apps that previously looked a little blurry on high-DPI displays. If

you notice that a desktop program isn’t scaling properly, you can use another new option that

debuted in version 1703 to change its behavior. Find the program’s executable file, right-click to

open its properties dialog box, click Change High DPI Settings on the Compatibility tab, select

the Override High DPI Scaling Behavior setting, and change it to System (Enhanced). This setting overrides the way the selected program handles DPI scaling, eliminating the use of bitmap

stretching and forcing the application to be scaled by Windows:

Windows 10 supports scaling factors from 100 percent all the way to 450 percent, with most elements of the user interface looking crystal-clear even at the highest scaling levels. That includes

Start, Cortana, File Explorer, and the Windows taskbar.

Windows registry

The Windows registry is the central storage location that contains configuration details for

hardware, system settings, services, user customizations, applications, and every detail—large

and small—that makes Windows work.

Understanding the Registry Editor hierarchy

Registry Editor (Regedit.exe) offers a unified view of the registry’s contents as well as tools for

modifying its contents. You’ll find this important utility on the All Apps list, under the Windows

Administrative Tools category. It also shows up when you use the search box. Alternatively, you

can type regedit at a command prompt or in the Run dialog box. Registry Editor has been virtually unchanged since the last century. However, beginning in version 1703, you might have

noticed some small but long-needed improvements: an address bar, new keyboard shortcuts

for traversing the registry, and the addition of a View-menu command with which you can

select the font for displaying the registry.

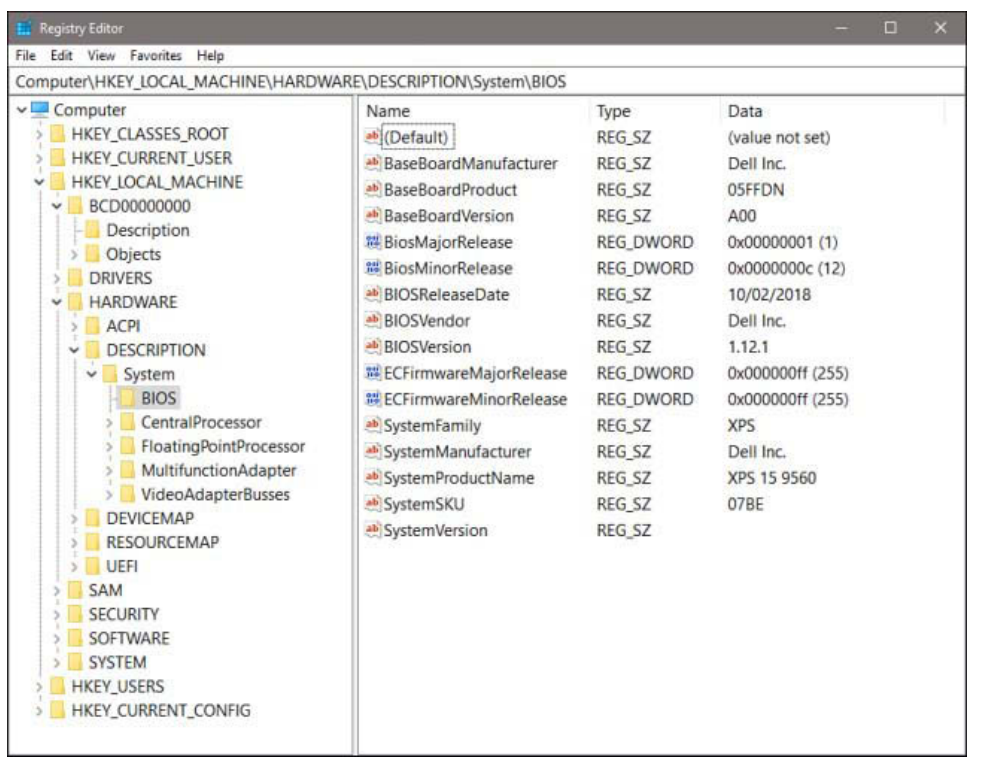

Figure 19-5 shows a (mostly) collapsed view of the Windows 10 registry, as seen through Registry Editor.

The Computer node appears at the top of the Registry Editor tree listing. Beneath it, as shown

here, are five root keys: HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT, HKEY_CURRENT_USER, HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE,

HKEY_USERS, and HKEY_CURRENT_CONFIG. For simplicity’s sake and typographical convenience, this book, like many others, abbreviates the root key names as HKCR, HKCU, HKLM,

HKU, and HKCC, respectively.

Root keys, sometimes called predefined keys, contain subkeys. Registry Editor displays this structure in a hierarchical tree in the left pane. In Figure 19-5, for example, HKLM is open, showing its

top-level subkeys.

Figure 19-5 The registry consists of five root keys, each of which contains many subkeys.

Subkeys, which we call keys for short, can contain subkeys of their own, which in turn can

be expanded as necessary to display additional subkeys. The address bar near the top of the

Registry Editor window shows the full path of the currently selected key: Computer\HKLM

HARDWARE\DESCRIPTION\System\BIOS, in the previous figure.

NOTE

One of the Registry Editor changes introduced in version 1703 is the address bar. In it,

you can type a registry path and press Enter to jump directly to that key, much as you

can for jumping to a folder in File Explorer. For the root keys, you can type the full name

or the commonly used abbreviations described earlier.

To go to the address bar and select its current content, press Alt+D or Ctrl+L, the same

keyboard shortcuts that work in File Explorer as well as most web browsers. Previous

versions of Registry Editor displayed the path in a status bar at the bottom of the screen,

but you couldn’t edit it or select it for copying.

The contents of HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE define the workings of Windows itself, and its subkeys

map neatly to several hives we mentioned at the start of this section. HKEY_USERS contains an

entry for every existing user account (including system accounts), each of which uses the security identifier, or SID, for that account.

The remaining three predefined keys don’t exist, technically. Like the file system in Windows—

which uses junctions, symlinks, and other trickery to display a virtual namespace—the registry

uses a bit of misdirection (implemented with the REG_LINK data type) to create these convenient representations of keys that are actually stored within HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE and

HKEY_USERS:

● HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT is merged from keys within HKLM\Software\Classes and HKEY_

USERS\sid_Classes (where sid is the security identifier of the currently signed-in user).

● HKEY_CURRENT_USER is a view into the settings for the currently signed-in user account,

as stored in HKEY_USERS\sid (where sid is the security identifier of the currently signed-in

user).

● HKEY_CURRENT_CONFIG displays the contents of the Hardware Profiles\Current subkey

in HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Hardware Profiles.

Any changes you make to keys and values in these virtual keys have the same effect as if you

had edited the actual locations. The HKCR and HKCU keys are generally more convenient to use.

Registry values and data types

Every key contains at least one value. In Registry Editor, that obligatory value is known as the

default value. Many keys have additional values. The names, data types, and data associated

with values appear in the right pane.

The default value for many keys is not defined. You can think of an empty default value as a

placeholder—a slot that could hold data but currently does not.

All values other than the default always include the following three components: name, data

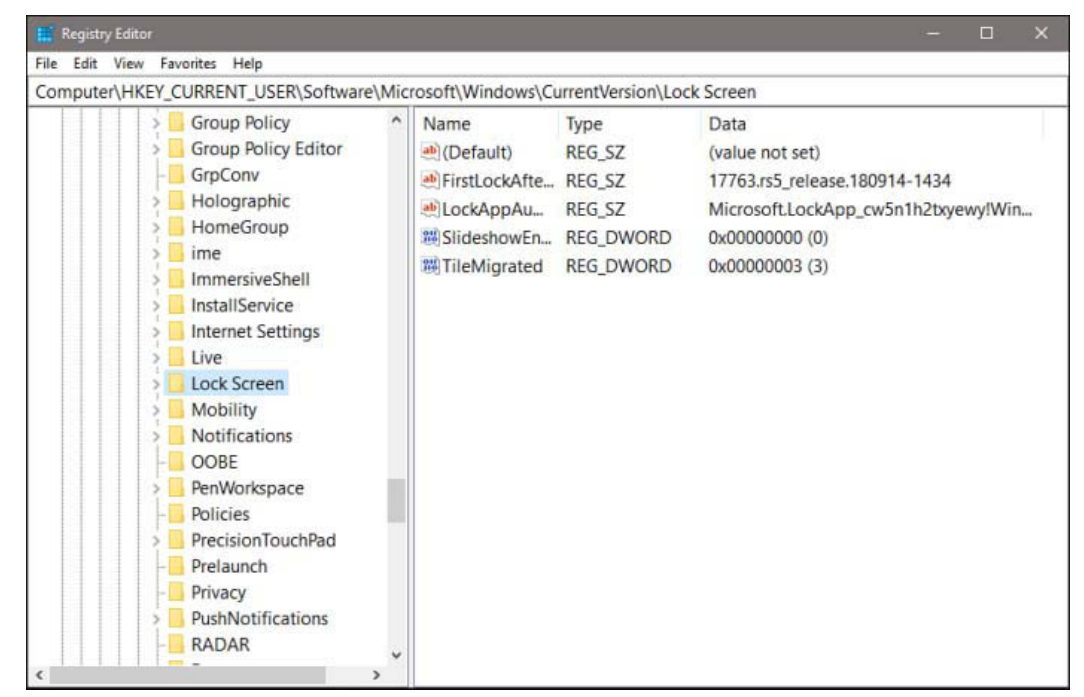

type, and data. Figure 19-6, for example, shows customized settings for the current user’s

lock screen. (Note the full path to this key in the address bar at the top of the Registry Editor

window.)

The SlideshowEnabled value (near the bottom of the list) is of data type REG_DWORD. The

data associated with this value (on the system used for this figure) is 0x00000000. The prefix 0x

denotes a hexadecimal value. Registry Editor displays the decimal equivalent of hexadecimal

values in parentheses after the value.

Selecting a key on the left displays all its values on the right.

The registry uses the following data types:

● REG_SZ. The SZ indicates a zero-terminated string. This variable-length string can contain

Unicode as well as ANSI characters. When you enter or edit a REG_SZ value, Registry Editor terminates the value with a 00 byte for you.

● REG_BINARY. The REG_BINARY type contains binary data—0s and 1s.

● REG_DWORD. This data type is a “double word”—that is, a 32-bit numeric value.

Although it can hold any integer from 0 to 232, the registry often uses it for simple Boolean values (0 or 1) because the registry lacks a Boolean data type.

● REG_QWORD. This data type is a “quadruple word”—a 64-bit numeric value.

● REG_MULTI_SZ. This data type contains a group of zero-terminated strings assigned to a

single value.

● REG_EXPAND_SZ. This data type is a zero-terminated string containing an unexpanded

reference to an environment variable, such as %SystemRoot%. (For information about

environment variables, see “Interacting with PowerShell” earlier in this chapter.) If you

need to create a key containing a variable name, use this data type, not REG_SZ.

Internally, the registry also uses REG_LINK, REG_FULL_RESOURCE_DESCRIPTOR, REG_

RESOURCE_LIST, REG_RESOURCE_REQUIREMENTS_LIST, and REG_NONE data types. Although you might occasionally see references in technical documentation to these data types, they’re

not visible or accessible in Registry Editor

Identifying the elements of a .reg file

As you review the examples shown in the two figures, note the following characteristics of .reg

files:

● Header line. The file begins with the line “Windows Registry Editor Version 5.00.” When

you merge a .reg file into the registry, Registry Editor uses this line to verify that the file

contains registry data. Version 5 (the version used with Windows 7 and later versions,

including Windows 10) generates Unicode text files, which can be used with all supported

versions of Windows as well as the now-unsupported Windows XP and Windows 2000.

● Key names. Key names are delimited by brackets and must include the full path from the

root key to the current subkey. The root key name must not be abbreviated. (Don’t use

HKCU, for example.) Figure 19-7 shows only one key name, but you can have as many as

you want.

● The default value. Undefined default values do not appear in .reg files. Defined default

values are identified by the special character @. Thus, a key whose default REG_SZ value

was defined as MyApp would appear in a .reg file this way:

“@”=”MyApp”

● Value names. Value names must be enclosed in quotation marks, whether or not they

include space characters. Follow the value name with an equal sign.

● Data types. REG_SZ values don’t get a data type identifier or a colon. The data directly

follows the equal sign. Other data types are identified as shown in Table 19-5.

Table 19-5 Data types identified in .reg files

Data type | Identifier

REG_BINARY | hex

REG_DWORD | dword

REG_QWORD | hex(b)

REG_MULTI_SZ | hex(7)

REG_EXPAND_SZ | hex(2)

A colon separates the identifier from the data. Thus, for example, a REG_DWORD value

named “Keyname” with value data of 00000000 looks like this:

“Keyname”=dword:00000000

● REG_SZ values. Ordinary string values must be enclosed in quotation marks. A backslash

character within a string must be written as two backslashes. Thus, for example, the path

C:\Program Files\Microsoft Office\ is written like this:

“C:\Program Files\Microsoft Office\“

● REG_DWORD values. DWORD values are written as eight hexadecimal digits, without

spaces or commas. Do not use the 0x prefix.

● All other data types. Other data types—including REG_EXPAND_SZ, REG_MULTI_SZ,

and REG_QWORD—appear as comma-delimited lists of hexadecimal bytes (two hex

digits, a comma, two more hex digits, and so on). The following is an example of a REG_

MULTI_SZ value:

“Addins”=hex(7):64,00,3a,00,5c,00,6c,00,6f,00,74,00,00,75,00,73,00,5c,00,

31,00,32,00,33,00,5c,00,61,00,64,00,64,00,64,00,69,00,6e,00,73,00,5c,00,

64,00,71,00,61,00,75,00,69,00,2e,00,31,00,32,00,61,00,00,00,00,00,00,00

● Line-continuation characters. You can use the backslash as a line-continuation character. The REG_MULTI_SZ value just shown, for example, is all one stream of bytes. We

added backslashes and broke the lines for readability, and you can do the same in your

.reg files.

● Line spacing. You can add blank lines for readability. Registry Editor ignores them.

● Comments. To add a comment line to a .reg file, begin the line with a semicolon.

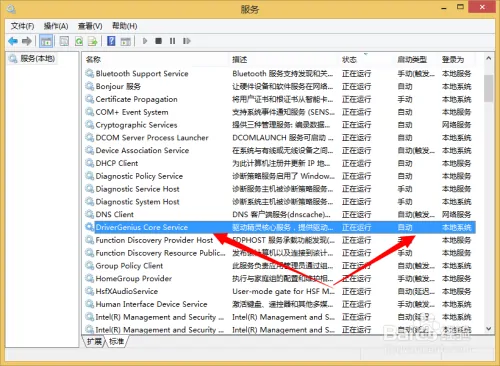

如何卸载windows的服务?卸载服务?

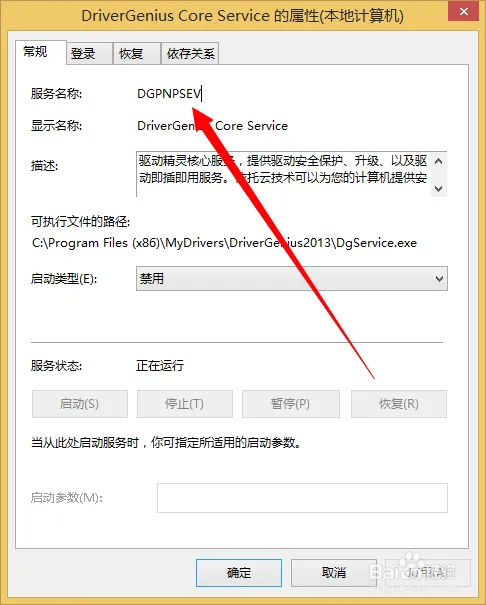

找到一个需要卸载的服务

双击打开

如何我们需要复制下来这个服务的名称

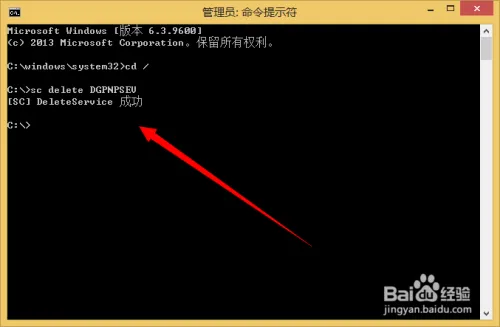

然后再cmd下输入 sc delete 服务名称来卸载服务

输入完成之后回车即可

卸载完成

安装到服务器的Windows Service卸载的时候出错了,结果在服务列表中就一直驻留,并且系统进程一直在运行,怎么都杀不掉。

最后终于找到办法了:

1.常规做法,批处理命令卸载

Net Stop ServiceName

sc delete ServiceName

pause

2.如果还是没办法,那就继续尝试

a.找到系统注册表,删掉服务的注册表信息,通常路径在:HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services 找到你的Service服务的名字,然后把整个文件夹删掉

b.如果还是在继续运行,service列表中还显示的话,用管理员权限打开cmd 命令 sc delete serviceName,如果提示 “the specified service is marked as deletion”。

导致windows service不能部署,也不能被删除,使用 SC 命令也不奏效。确实冒了一把冷汗。经过10几分钟的折腾,终于弄明白了:原来是windows service database缓存的原因,reboot server可以完美解决问题。但实际上我们可以尝试:

关闭所有windows service控制面板。

查找windows service的PID:SC queryex service_name

杀掉进程:taskkill /PID service_pid /f

这样就再也不用担心windows service部署了。

至此就可以完全卸载掉了。

Win10的序列号查询

本机的Win10的序列号很容易查出来,按“Win”+ “R”,运行powershell,然后执行以下命令:

(Get-WmiObject -query ‘select * from SoftwareLicensingService’).OA3xOriginalProductKey

输入法

半角状态就是说输入法状态条中,那半月形变为圆形时为全角这时输入的英文字母及数字与汉字等大,半角当然是输入法状态条中为半月形时的状态了,这时输入的英文字母及数字不与汉字等大为汉字一半(全角占用两个字节)。